Apologies for interrupting your experience.

This publication is currently being maintained by the Magloft team. Learn more about the technology behind this publication.

Manage your subscription to this publication here or please contact the publisher Resuscitation Council for an update.

Cardiac arrest rhythms –

monitoring and recognition

In this chapter

ECG monitoring

Diagnosis from cardiac monitors

Cardiac arrest rhythms

The learning outcomes will enable you to:

Understand the reasons for ECG monitoring

Monitor the ECG

Recognise the rhythms associated with cardiac arrest

Introduction

ECG monitoring enables identification of the cardiac rhythm in patients in cardiac arrest. Monitoring patients at risk of developing arrhythmias can enable treatment before cardiac arrest occurs. Patients at risk of cardiac arrest include those with chest pain, collapse or syncope, palpitations, or shock (e.g. due to bleeding or sepsis).

Basic, single-lead ECG monitoring will not detect cardiac ischaemia reliably. Record serial 12-lead ECGs in patients experiencing chest pain suggestive of an acute coronary syndrome. In all patients who have persistent arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythm) and are at risk of deterioration, establish ECG monitoring and, as soon as possible, record a good-quality 12-lead ECG. Monitoring alone will not always enable accurate rhythm recognition and it is important to document the arrhythmia in 12-leads for future reference.

Accurate analysis of cardiac rhythm abnormalities requires experience, but by applying basic principles most rhythms can be interpreted sufficiently to enable selection of the appropriate treatment. The inability to reliably recognise VF/pVT is a major drawback in the use of manual defibrillators. Automated external defibrillators (AEDs) overcome this problem by automatic analysis of the rhythm. For a shockable rhythm, the defibrillator charges to a pre-determined energy and instructs the operator that a shock is required. The introduction of AEDs has meant that more people can now apply defibrillation safely. People who lack training or confidence in recognising cardiac rhythms should use AEDs.

Accurate analysis of some rhythm abnormalities requires experience and expertise; however, the non-expert can interpret most rhythms sufficiently to identify what immediate treatment is needed. The main priority is to recognise that the rhythm is abnormal and that the heart rate is inappropriately slow or fast. Use the structured approach to rhythm interpretation described in this chapter to help you to avoid errors. Any need for immediate treatment will be determined largely by the effect of the arrhythmia on the patient rather than by the nature of the arrhythmia. When an arrhythmia is present, first assess the patient (use the ABCDE approach), and then interpret the rhythm as accurately as possible.

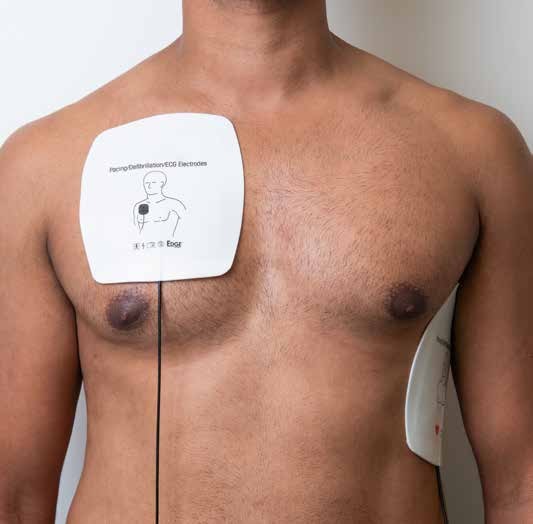

Figure 8.1 Electrode positions

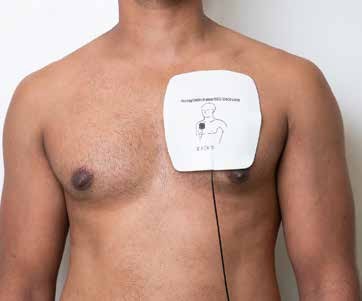

Figure 8.2 Pectoral and apical positions for defibrillator pads

ECG monitoring

Planned ECG monitoring

Attach ECG electrodes to the patient using the positions shown in Figure 8.1. These will enable monitoring using ‘modified limb leads’ I, II and III. Make sure that the skin is dry, not greasy (use an alcohol swab and/or abrasive pad to clean), and either place the electrodes on relatively hair-free skin or shave off dense hair. Place electrodes over bone rather than muscle, to minimise interference in the ECG signal from muscle artefact. Different electrode positions may be used when necessary (e.g. trauma, recent surgery, skin disease).

Most ECG leads are colour-coded to help with correct connection

The usual colours are: Red for the Right arm lead (usually placed over the right shoulder joint)

yeLLow for the Left arm lead (usually placed over the left shoulder joint)

Green for the leG lead (usually placed on the abdomen or lower left chest wall). (Figure 8.1)

Begin by monitoring in modified lead II as this usually displays good amplitude sinus P waves and good amplitude QRS complexes, but switch to another lead if necessary to obtain the best ECG signal. Try to minimise muscle and movement artefact by explaining to patients what the monitoring is for and by keeping them warm and relaxed.

Figure 8.3a, b & c Anterior-posterior (AP) pad positions for external pacing.

a Front view

b Side View

c Back view

Emergency monitoring

In an emergency, such as a collapsed patient, assess the cardiac rhythm as soon as possible by applying self-adhesive defibrillator pads in the usual position mentioned in Chapter 3 (Figures 8.2 and 8.3). Monitor the cardiac rhythm continuously with proper ECG electrodes as soon as possible after cardiac arrest.

Diagnosis from cardiac monitors

The displays and printouts from cardiac monitors are suitable only for recognition of rhythms and not for more detailed ECG interpretation.

Basic electrocardiography

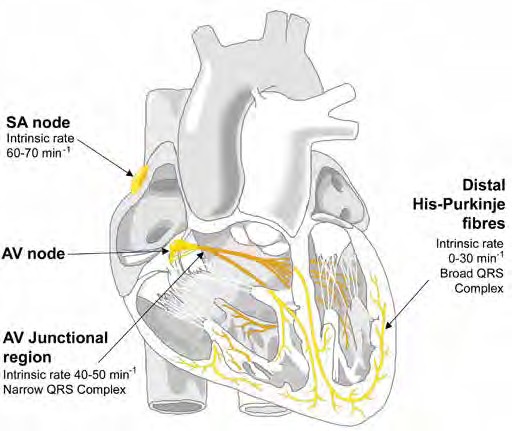

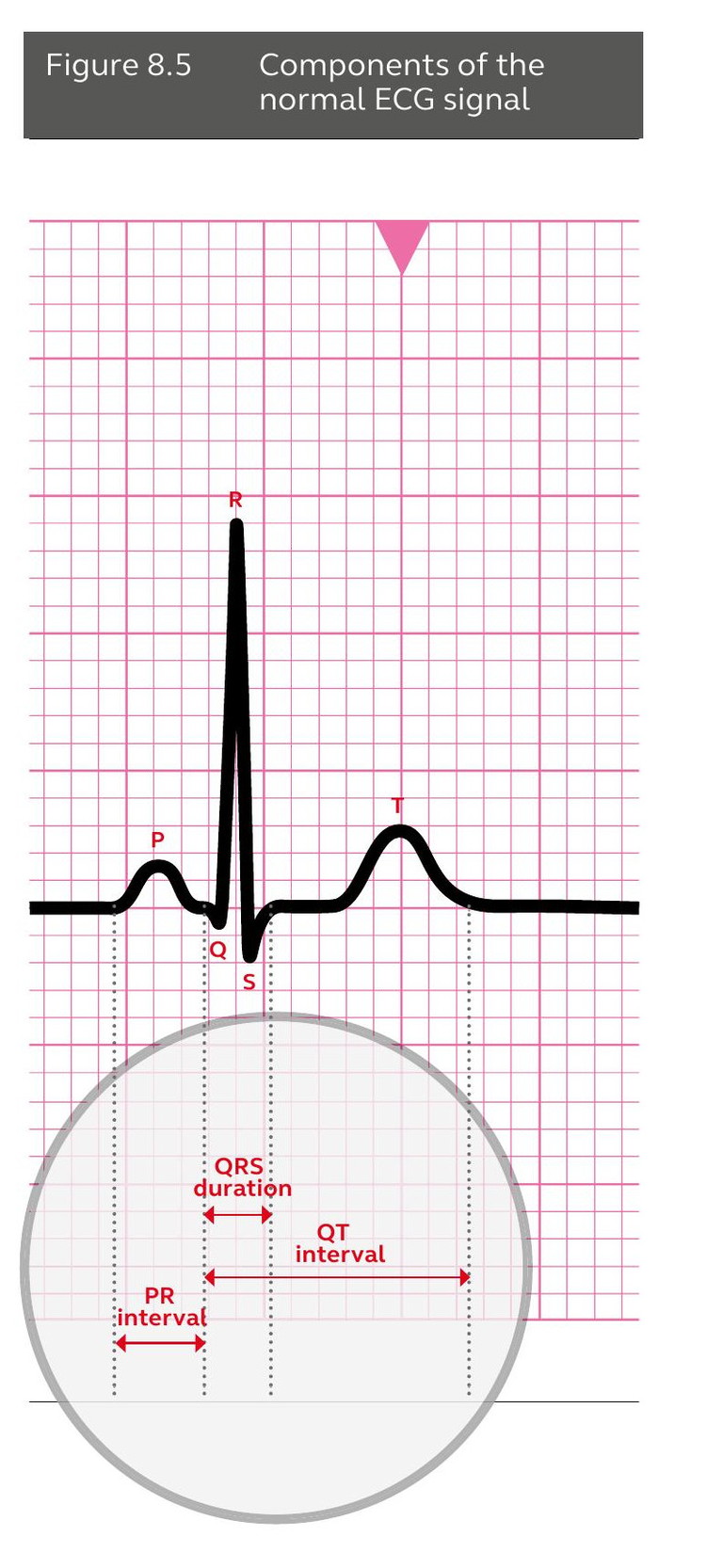

The normal adult heart rate is defined as 60–100 min-1. A rate below 60 min-1is a bradycardia and a rate of 100 min-1or more is a tachycardia. Under normal circumstances depolarisation is initiated from a group of specialised pacemaker cells, the sinoatrial (SA) node, in the right atrium (Figure 8.4). The wave of depolarisation spreads from the SA node into the atrial muscle; this is seen on the ECG as the P wave (Figure 8.5). Atrial contraction is the mechanical response to this electrical impulse.

The electrical impulse is spread to the ventricular muscle along specialised conducting tissue through the atrioventricular (AV) node and His-Purkinje system. The bundle of His bifurcates to enable depolarisation to spread into the ventricular muscle along two specialised bundles of conducting tissue the right bundle branch to the right ventricle and the left bundle to the left ventricle.

Depolarisation of the ventricles is reflected in the QRS complex of the ECG. The normal sequence of cardiac depolarisation described above is known as sinus rhythm. The T wave that follows the QRS complex represents ventricular repolarisation.

The specialised cells of the conducting tissue (the AV node and His-Purkinje system) enable coordinated ventricular depolarisation, which is more rapid than uncoordinated depolarisation. With normal depolarisation, the QRS complex is narrow, which is defined as less than 0.12 seconds. If one of the bundle branches is diseased, conduction delay causes a broad QRS complex (i.e. greater than 0.12 seconds (3 small squares on the ECG)).

Figure 8.4 Electrical conduction in the heart / cardiac conducting system

Cardiac arrest rhythms

The rhythms present during cardiac arrest are classified into two groups:

• Shockable rhythms: ventricular fibrillation (VF) and pulseless ventricular tachycardia (pVT)

• Non-shockable rhythms: asystole and pulseless electrical activity (PEA).

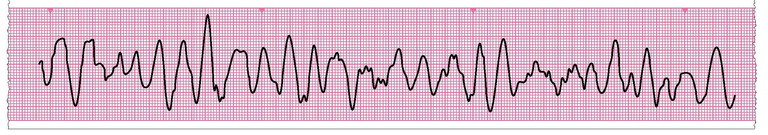

Ventricular fibrillation (VF)

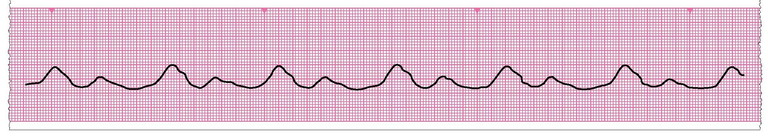

In VF the ventricular myocardium depolarises randomly. The ECG shows rapid, bizarre, irregular waves of widely varying frequency and amplitude (Figure 8.6, Figure 8.12). VF is sometimes classified as coarse or fine depending on the amplitude (height) of the complexes. If the rhythm is clearly VF (irrespective if coarse or fine), attempt defibrillation.

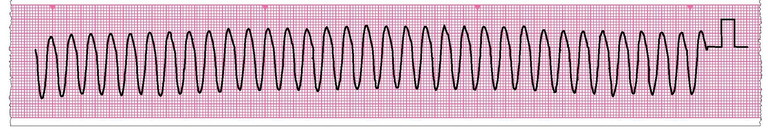

Pulseless ventricular tachycardia (pVT)

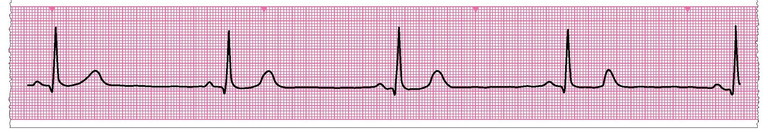

Ventricular tachycardia, particularly at higher rates or when the left ventricle is compromised, may cause profound loss of cardiac output. Pulseless VT is managed in the same way as VF. The ECG shows a broad-complex tachycardia. In monomorphic VT, the rhythm is regular (or almost regular) at a rate of 100–300 min-1(Figure 8.7).

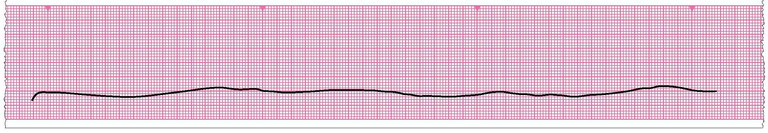

Asystole

Usually there is neither atrial nor ventricular activity, and the ECG is a more of a straight line (Figure 8.8).

Deflections that can be confused with very fine VF can be caused by baseline drift, electrical interference, respiratory movements, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation. A completely straight line usually means that a monitoring lead has disconnected. Whenever asystole is suspected, check that the gain on the monitor is set correctly (1 mV cm-1) and that the leads are connected correctly. If the monitor has the facility, view another lead configuration.

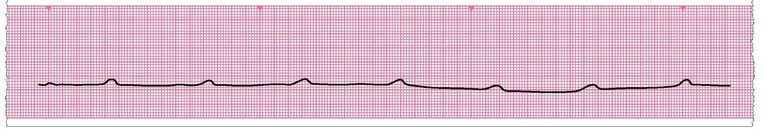

Atrial activity (i.e. P waves), may continue for a short time after the onset of ventricular asystole; there will be P waves on the ECG but no evidence of ventricular depolarisation (Figure 8.9). These patients may be suitable for cardiac pacing.

Figure 8.6 Ventricular fibrillation (VF)

Figure 8.7 Ventricular tachycardia (VT)

Figure 8.8 Asystole

Pulseless electrical activity (PEA)

The term pulseless electrical activity (PEA) does not refer to a specific cardiac rhythm. It defines the clinical absence of cardiac output despite electrical activity that would normally be expected to produce a cardiac output.

Potentially treatable causes include severe fluid depletion or blood loss, cardiac tamponade, massive pulmonary embolism and tension pneumothorax.

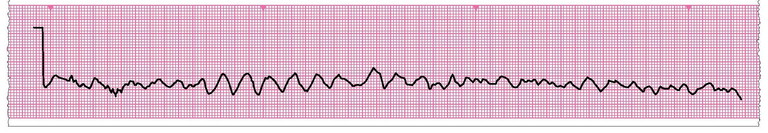

Agonal rhythm

Agonal rhythm occurs in dying patients. Agonal rhythm is characterised by slow, irregular, wide ventricular complexes of varying shape (Figure 8.11). This does not generate a pulse. It is usually seen during the late stages of unsuccessful resuscitation. The complexes slow inexorably becoming progressively broader until all recognisable electrical activity is lost.

Bradycardia

The treatment of bradycardia (a slow heart rate – less than 60 min-1) (Figure 8.10) depends on its haemodynamic consequences. Very slow rates can cause the blood pressure to fall. It is not a true cardiac arrest rhythm as patients usually have a pulse. Bradycardia may however mean imminent cardiac arrest and needs to be treated with atropine or other measures (e.g. pacing) in patients with adverse features (e.g. low blood pressure, fainting, chest pain, heart failure).

Figure 8.9 Ventricular standstill with continuing sinus P waves

Figure 8.10 Sinus bradycardia

Figure 8.11 Agonal rhythm

Figure 8.12 Fine ventricular fibrillation

Example of Sinus rhythm