Apologies for interrupting your experience.

This publication is currently being maintained by the Magloft team. Learn more about the technology behind this publication.

Manage your subscription to this publication here or please contact the publisher Resuscitation Council for an update.

Immediate resuscitation

In this chapter

Features specific to resuscitation by trained responders

Sequence for the collapsed patient in a healthcare setting

The mechanism of defibrillation and factors affecting defibrillation success

The sequence for safe use of automated external defibrillators (AED) and/or manual defibrillators

The learning outcomes will enable you to:

Start immediate resuscitation

Give high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) with minimal interruption

Understand how to safely deliver a shock with an AED and/or manual defibrillator

Understand the importance of minimising pauses in chest compressions during CPR/ defibrillation

Continue resuscitation until more experienced help arrives

Introduction

After cardiac arrest, the division between basic life support and advanced life support is arbitrary. The public expect that all clinical staff know how to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

For every cardiac arrest, ensure that:

– cardiac arrest is recognised immediately

– help is summoned using a standard telephone number in acute hospitals (2222 in the UK). In community hospitals, help is usually summoned dialling 999 for ambulance

– CPR is started immediately and, if indicated, defibrillation is attempted as soon as possible (within 3 minutes).

Following the onset of ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VF/pVT), cardiac output ceases and cerebral hypoxic injury starts within 3 minutes. For complete neurological recovery, early successful defibrillation with return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is essential. Defibrillation is a key link in the Chain of Survival and is one of the few interventions proven to improve outcome from VF/pVT cardiac arrests. The shorter the interval between the onset of VF/pVT and delivery of the shock, the greater the chance of successful defibrillation and survival.

Defibrillators with automated rhythm recognition (automated external defibrillators (AEDs)) are reliable, computerised devices designed to use voice and visual prompts to guide lay rescuers and healthcare professionals to attempt defibrillation safely in cardiac arrest patients (Figure 3.1). Sufficient staff should be trained to enable the first shock to be delivered within 3 minutes of collapse anywhere in a healthcare setting.

This chapter is for healthcare professionals who are first to respond to a cardiac arrest. It is applicable to healthcare professionals working in hospitals as well as those working in other clinical settings such as community hospitals, mental health premises and dental professionals etc.

Figure 3.1 Use of AED during immediate resuscitation

Why is in-hospital resuscitation different?

The exact sequence of actions after cardiac arrest depends on several factors and this will vary depending on the setting, particularly if in an acute hospital compared to a community healthcare setting. Other factors that will influence the response are:

• location (clinical/non-clinical area; monitored/ unmonitored area)

• skills of the first responders

• number of responders

• equipment available

• rapid response system to cardiac arrest and medical emergencies (e.g. medical emergency team (MET), resuscitation team).

Location of cardiac arrest

Patients who have a witnessed or monitored cardiac arrest in an acute care area are usually diagnosed and treated quickly. Ideally, all patients who are at high risk of cardiac arrest should be cared for in a monitored area where staff and facilities for immediate resuscitation are available. Patients, visitors or staff may also have a cardiac arrest in non-clinical areas (e.g. car parks, corridors) and you may have to move the patient to enable continued resuscitation.

Guidance for safer handling during resuscitation in healthcare settings is available from Resuscitation Council UK: https://www.resus.org.uk/library/publications/publication-guidance-safer-handling.

Skills of first responders

All staff should be able to recognise cardiac arrest, call for help and start resuscitation. They should do what they have been trained to do. For example, if you work in critical care and emergency medicine you may have more advanced resuscitation skills and greater experience in resuscitation than those who use resuscitation skills rarely. Use the skills you are trained to do. Only use a manual defibrillator if you are trained/competent and confident in its use, otherwise you should use an AED or a manual defibrillator in AED mode.

Number of responders

If you are alone, always make sure that help is coming. Usually, colleagues are nearby and several actions can be undertaken simultaneously.

Equipment available

Staff should have immediate access to resuscitation equipment and medications. Ideally, the equipment used for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (including defibrillators) and the layout of equipment and drugs should be the same throughout the hospital. You should be familiar with the resuscitation equipment used in your clinical area.

Serious patient safety incidents associated with CPR and patient deterioration are commonly associated with equipment problems during resuscitation (e.g. portable suction not working, defibrillator pads missing). Specially designed trolleys or sealed tray systems can improve speed of access to equipment and reduce adverse incidents. Resuscitation and equipment must be checked on a regular basis to ensure it is ready for use.

AEDs can be used in clinical and non-clinical areas where staff do not have rhythm recognition skills, or rarely need to use a defibrillator. This type of defibrillator is often found in community settings and are usually in wall mounted cabinets that sometimes require a keycode from the ambulance service. The use of AEDs can deliver a much needed shock during the precious minutes before the arrival of the resuscitation team or paramedics.

Waveform capnography is a monitor that is routinely used during anaesthesia and for critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation. It must be used to confirm correct tracheal tube placement during resuscitation and can also help guide resuscitation interventions (Chapter 7). Waveform capnography monitoring is available on newer defibrillators, as part of portable monitors or as a hand-held device.

After successful resuscitation, patients often need transferred to other clinical areas (e.g. intensive care unit) or other hospitals. Ensure transfer equipment and drugs are available to enable this. In community settings, patients will be transferred to hospital by the ambulance service who will usually provide their own equipment.

At the end of every resuscitation attempt, ensure equipment and drugs are replaced and available to use the next time they are needed.

Resuscitation team

The resuscitation team can be a traditional cardiac arrest team, which is only called when cardiac arrest is recognised. In some hospitals a rapid response team (e.g. medical emergency team (MET)) is called if a patient is deteriorating before cardiac arrest occurs.

Resuscitation team members should meet for introductions and plan before they attend actual events. Knowing each other’s names, skills/experience and discussing how the team will work together during a resuscitation will improve teamwork during resuscitation attempts. Team members should debrief after each event, to enable performance and concerns to be discussed openly. This has most benefit when discussions are based on data collected during the event (Chapter 4).

Principles of safe and effective defibrillation

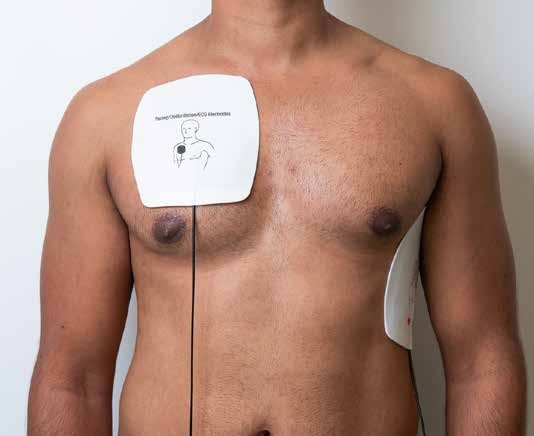

Figure 3.2 Standard electrode position

Defibrillation is the passage of an electrical current across the myocardium to depolarise a critical mass of heart muscle simultaneously, enabling the natural ‘pacemaker’ tissue to resume control.

Factors affecting defibrillation success

Defibrillation success depends on sufficient current being delivered to the myocardium. Factors affecting defibrillation success include transthoracic impedance, electrode position, the shock energy, and the shock sequence.

Transthoracic impedance

Transthoracic impedance is the resistance of the thorax to electric current flow. Some defibrillators measure the transthoracic impedance and adjust their output accordingly, which is known as impedance compensation. To minimise the impedance:

• Ensure good contact between self-adhesive pads and the patient’s skin. Use the self-adhesive pads recommended by the manufacturer for the specific defibrillator.

• If the patient has a very hairy chest, and a razor is immediately available, use it to shave the area where the electrodes are placed. Make sure chest compressions continue whilst shaving the chest. However, defibrillation should not be delayed if a razor is not to hand immediately.

• Remove drug-eluting patches or transdermal patches if in the area where the self-adhesive pads would be applied. If this is likely to delay defibrillation, place the pads in an alternative position that avoids the patch.

Electrode position

The electrodes (also called defibrillator pads, self-adhesive pads) are positioned for greatest current flow through the myocardium. The standard positions are one electrode to the right of the upper sternum below the clavicle, and the other (left apical) in the mid-axillary line, approximately level with the V6 ECG electrode and clear of breast tissue. The apical electrode must be sufficiently lateral (Figure 3.2). Other acceptable positions include:

Figure 3.3 Alternative electrode position – bi-axillary

• One electrode anteriorly, over the left precordium, and the other electrode on the back behind the heart, just inferior to the left scapula (antero-posterior) (Figure 8.3a,b,c).

• One electrode placed in the standard apical position, and the other electrode on the back, over the right scapula (postero-lateral).

• The lateral chest walls, one on the right and the other on the left side (bi-axillary) (Figure 3.3).

Shock sequence

For all cardiac arrests start CPR immediately. Use the defibrillator to assess the rhythm as soon as it arrives. Although defibrillation is key to the management of patients in VF/pVT, continuous, uninterrupted chest compressions are also required to optimise the chances of successful resuscitation. Even short interruptions in chest compressions (e.g. to deliver rescue breaths or perform rhythm analysis) reduce the chances of successful defibrillation. The aim is to ensure that chest compressions are performed continuously throughout the resuscitation attempt, pausing briefly only to enable specific interventions.

Another factor that is critical in determining the success of defibrillation is the duration of the interval between stopping chest compressions and delivering the shock: the pre-shock pause. Every 5 second increase in the pre-shock pause almost halves the chance of successful defibrillation. Consequently, defibrillation must always be performed quickly and efficiently in order to maximise the chances of successful resuscitation. If there is any delay in obtaining a defibrillator, and while the defibrillator pads are being applied, continue high-quality chest compressions and ventilation.

Defibrillator safety

Do not deliver a shock if anybody is touching the patient. Do not hold intravenous infusion equipment or the patient’s trolley/bed during shock delivery. The operator must ensure that everyone is clear of the patient before delivering a shock. Wipe any water or fluids from the patient’s chest before attempting defibrillation. The gloves routinely available in clinical settings do not provide sufficient protection from the electric current, therefore a shock must only be delivered when everyone is clear of the patient.

Safe use of oxygen during defibrillation

Sparks in an oxygen-enriched atmosphere can cause fire and burns to the patient. Self-adhesive pads are far less likely to cause sparks than manual paddles – no fires have been reported in association with the use of self-adhesive pads. The following precautions reduce the risk of fire:

• Remove any oxygen mask or nasal cannulae and place them at least 1 metre away from the patient’s chest.

• Leave the self-inflating bag connected to the tracheal tube or well-fitted supraglottic airway as no increase in oxygen concentration occurs in the zone of defibrillation, even with an oxygen flow of 15 L min-1. Alternatively, disconnect the ventilation bag from the tracheal tube or supraglottic airway and remove it at least 1 metre from the patient’s chest during defibrillation.

• If the patient is connected to a ventilator, for example in the operating room or critical care unit, leave the ventilator tubing (breathing circuit) connected to the tracheal tube unless chest compressions prevent the ventilator from delivering adequate tidal volumes. In this case, the ventilator is usually substituted by a self-inflating bag, which can be left connected or detached and removed to a distance of at least 1 metre. If the ventilator tubing is disconnected, ensure that it is kept at least 1 metre from the patient or, better still, switch the ventilator off; modern ventilators generate massive oxygen flows when disconnected.

Automated rhythm analysis

It is almost impossible to shock inappropriately with an AED. Movement is usually sensed, so movement artefact is unlikely to be interpreted as a shockable rhythm.

Implanted electronic devices

When a patient needs external defibrillation, effective measures to try to restore life take priority over concerns about any implanted device such as a pacemaker, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), implantable event recorder or neurostimulator. Current resuscitation guidelines are followed, but awareness of the presence of an implanted device allows some additional measures to optimise outcome:

• To minimise the risk of damage to the device, place the defibrillator electrodes away from the pacemaker or ICD generator (at least 8 cm) without compromising effective defibrillation. If necessary, place the pads in the antero-posterior, postero-lateral or bi-axillary position as described above.

• An ICD gives no warning when it delivers a shock. In an emergency, a ring magnet can be placed over the ICD to disable the defibrillation function if required. Deactivation of an ICD in this way does not disable the ability of the device to act as a pacemaker if it has that capability.

• During a shockable rhythm, external defibrillation should be attempted in the usual way if the ICD has not delivered a shock, or if its shocks have failed to terminate the arrhythmia.

Sequence for collapsed patient

An algorithm for the initial management of cardiac arrest is shown in Figure 3.4.

1. Ensure personal safety

• There are very few reports of harm to rescuers during resuscitation.

• Your own safety and that of resuscitation team members is the first priority.

• Check that the patient’s surroundings are safe.

Put on personal protective equipment (PPE) (e.g. gloves, eye protection, face masks, aprons, gowns) as appropriate. Follow national and local infection control measures and PPE guidelines from your employer.

• Be careful with sharps; a sharps box must be available.

• Use safe handling techniques for moving individuals during resuscitation.

• Avoid contact with corrosive chemicals (e.g. strong acids, alkalis, paraquat) or substances such as organophosphates that are easily absorbed through the skin or respiratory tract.

• Defibrillator safety as discussed above.

Resuscitation Council

We're with you for life.

Resuscitation Council UK is saving lives by developing guidelines, influencing policy, delivering courses and supporting cutting-edge research. Through education, training and research, we’re working towards the day when everyone in the country has the skills they need to save a life.

Categories

Explore our inspiring content by topic